In 1972, then-editor of The Atlanta Constitution Reg Murphy said Atlanta may be on the “very edge of becoming a movie city.”

In an editorial ahead of the release of the North Georgia-filmed thriller “Deliverance,” Murphy was confident in what the city could become despite lacking infrastructure.

“But the talent follows the action,” Murphy wrote. “Get the city embarked on a major effort to attract the big companies, and the professionals would be available immediately.”

It took longer than Murphy probably expected, but more than 50 years later, film and television have become a multibillion-dollar industry, and one of the state’s greatest cultural exports, propelled by a generous, albeit controversial, tax credit.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has followed the industry closely for a century, including its rise into a production hub over the past two decades, as well as its uncertain future.

Early days

Georgia’s first brushes with the film industry go back more than a century. It entered the movie-making business in 1918 with the silent war film “Over the Top,” which shot its trench scenes at Camp Wheeler near Macon.

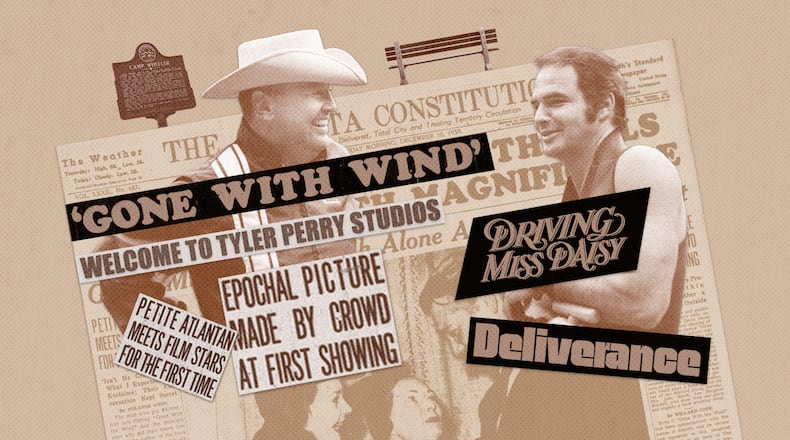

Decades later, Hollywood came back when “Gone With the Wind” made its debut here in 1939. An estimated 300,000 people lined the streets to catch glimpses of stars Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh. The Journal and Constitution for weeks covered the hullabaloo. The papers even reported the premiere’s seating chart.

But the first real boom period for moviemaking in Georgia started in the 1970s. This era produced projects canonized in Hollywood history, such as “Deliverance” and “Smokey and the Bandit,” along with the original five episodes of “Dukes of Hazzard.”

“Deliverance,” which filmed along the Chattooga River in the summer of 1971 and starred Burt Reynolds, Ned Beatty and Jon Voight, was the prelude of what was set to come. On the set of this film, Ed Spivia, then a state tourism official, noticed the impact that productions in Georgia could have on local spending. The cast and the crew, including Reynolds, were patronizing restaurants and other businesses.

So Spivia took his finding to then-Gov. Jimmy Carter, who would eventually tap Spivia to lead the state’s first film commission.

Credit: Archive Photos

Credit: Archive Photos

Spivia began visiting Hollywood to build relationships and pitch the state as a place to do business. By the time Carter was inaugurated president, more than a handful of movies set up shop in the state.

Reynolds became a vocal advocate for Georgia. Soon, Richard Pryor, Tatum O’Neal and other stars filmed projects here.

The television drama “In the Heat of the Night” later moved from Louisiana to Covington. Two Oscar-winning films were shot in the state: 1989’s “Driving Miss Daisy,” which was also set in Atlanta, and 1994’s “Forrest Gump.”

During this time, Atlanta’s own Coca-Cola acquired Columbia Pictures, one of the leading film studios in the world. The company paid $750 million for the studio in 1982 and sold it to Sony less than a decade later.

Business began drying up in the late 1990s, which perplexed some locals, said Ric Reitz, an actor who has worked in the industry for more than 40 years. It turns out productions were chasing after newly passed tax credits in Canada and other countries that were subsidizing the arts.

Race for incentives

After watching North Carolina and Louisiana increase their efforts to lure Hollywood projects, Georgia passed its first round of tax-incentive legislation in 2005.

Georgia supersized the credit in 2008.

That year, the Peach State raised its transferable tax credit to up to 30%, a move that would turn the state into a heavyweight champ in the international production arena.

The effect of the credit was felt almost immediately. Projects flooded the state, including “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire” and the sequel to the Will Ferrell comedy “Anchorman.” More than a dozen industry-specific supplier companies expanded or relocated to the state. Soundstages began cropping up across the metro area.

Spending from productions more than doubled, from $413 million in fiscal year 2008 to about $933.9 million five years later. In 2022, spending hit its record of $4.4 billion.

Reitz, who helped shape the 2008 credit, said the state wasn’t surprised the measure would be successful. But they didn’t anticipate how far it would take off.

“Our grand goal was: Is it possible for us to get to a billion dollars?” Reitz said. “We thought we could with the right package.”

Meanwhile, actor and playwright Tyler Perry was on his way to becoming one of the state’s most recognizable figures. Perry first came to Atlanta for Freaknik, he told the AJC in an email, and the city showed him the possibilities he’d always dreamed of.

Perry went from financing plays from his life savings to generating more than $500 million at the box office for his self-written and directed films, all of which were filmed in the state.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Perry was an early pioneer in Georgia’s soundstage business, converting 330 acres of Fort McPherson, a former Army post in southwest Atlanta, into one of the largest studios in the United States.

The 2019 grand opening, which the AJC covered, was attended by Denzel Washington and Will Smith, Beyoncé and Jay-Z, former President Bill Clinton and other elites.

A few reasons have made Georgia Perry’s home base for more than two decades, he said: It’s a convenient city to get to from anywhere in the world, and the people.

“The warmth fosters great relationships and great people to work with and for,” Perry said. “And that inspires a lot of what I write about.”

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

‘Wild West’

In the years after the new tax credit, the film industry seemed to spark an entrepreneurial spirit in Atlanta, said Jennifer Brett, a former AJC reporter and deputy managing editor who wrote about the entertainment industry for more than a decade.

People with no prior film experience jumped in to fill gaps Hollywood needed.

Speculators fashioned soundstages out of empty warehouses. Wedding caterers were tapped to run food services on sets and at red carpet premieres. Stylists from nearby salons became hair and makeup pros.

“Atlanta has never been light on entrepreneurial spirit,” said Brett, who is now news director of the Tennessean in Nashville. “It’s the kind of place where the business of Atlanta is business, and it’s always interesting to see just people getting in on the action.”

Reitz said the early days felt like the Wild West.

“We could do anything, and it didn’t matter what (critics) said, we were going to succeed,” Reitz said.

Georgia hit it big in the mid-2010s with Marvel Studios. The studio filmed at least one blockbuster in the state every year — including the $2 billion-generating “Avengers: Endgame” and “Black Panther” — until peeling back its production slate.

Credit: Marvel Studios

Credit: Marvel Studios

Growing pains

Georgia’s film incentives weren’t without controversy. Critics said film industry incentives fail to encourage economic growth because productions largely create temporary or part-time work — rather than permanent jobs — that are sometimes filled by people from other states. Local governments began awarding tax breaks to build soundstages to support the burgeoning industry, which also brought opposition.

As production spending topped $4 billion after the pandemic, lawmakers tried to curtail the money the state was awarding in tax credits by putting a cap on the program. This effort did not pass.

Tragedies changed the industry, too. In 2014, a 27-year-old crew member was killed on the set of the Greg Allman biopic “Midnight Rider” after being hit by a speeding train. The director was shooting a scene on an active railroad bridge without permission from the railway company. Her death sparked grief and calls for stronger safety measures on film sets nationwide, and the film was never completed.

Credit: Katelyn Myrick

Credit: Katelyn Myrick

The future

In the months leading up to the 2023 writers and actors strikes, business slowed in Georgia and the U.S. at large before it came to a halt.

After the strikes, the economics of the industry began to shift: Fewer projects were being launched, and larger-budget blockbusters moved overseas to countries with bigger incentives and cheaper labor.

Other states have upgraded their incentives, including California and New York, while Georgia has kept its tax credit largely the same. In the past year-and-a-half, lawmakers have tweaked Georgia’s program, including streamlining the auditing process and passing a separate credit for postproduction.

Work has returned to Georgia, but at a significantly reduced pace. Industry professionals have struggled to stay afloat, and soundstage owners are pivoting to find ways to pay the bills.

Still, there’s hope for the future.

“We’re back to where we were, really, in the late ’90s and early millennium. It took 25 years to make that cycle,” Reitz said. “But we’re still on the lips of people within the industry, some positive, some negative.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured